December – Creative Process

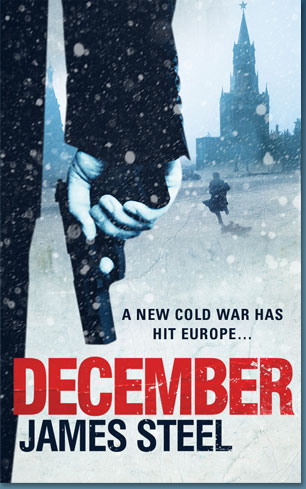

The first Alex Devereux Novel

The creative process behind ‘December’

by James Steel

How do you go about writing a book?

Good question.

My plots are very ideas driven. They are really ways for me to talk about historical, political and intellectual things that I am into at the time.

So what’s the big idea with my new book ‘December’? Well, for starters, here’s the tagline(s): Russia turns off the gas to Britain. In revenge the British government send an embittered mercenary, Alex Devereux, to start a modern Russian Revolution.

This plot came about because I am a news junkie and into Russian history. The creative spark that brought the two together was an article in the back of The Times a little while ago. It mentioned that the prison in Siberia that Mikhail Khodorkovsky had just been sent to was the same one that the Decembrist rebels in 1825 had been imprisoned in. Khodorkovsky is an oligarch jailed on trumped up charges because he dared oppose Putin politically. The Decembrists were liberal constitutionalists opposed to Tsarist dictatorship and I liked the similarity between the two.

That got me thinking and what with the repeated Russian energy blockades of Europe and my existing British mercenary character, Alex Devereux, I realised I had a story. Alex has the fate of Europe placed in his hands by the British government; he is their last chance of stopping the new Russian dictator, Viktor Krymov. Working with an unstable Russian oligarch and his former lover, Alex and his team have to launch a raid on the prison camp, free a famous political prisoner and get him to Moscow to launch a revolution against a new dictatorship. He is carried along in a race against time that leads to a final violent showdown in Moscow and a fight for the soul of the Russian nation. I like blending action and ideas in the story into a large-scale narrative.

So, going back to the ideas thing, all this gave me an excuse to talk about Russian history and politics. I wanted to look at how Russia’s history of being invaded and trashed by pretty much everyone has left them with a defensive attitude to foreigners that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. I also wanted to discuss how the Putin government works and what problems it has created for Russian society now.

The final thing I wanted to talk about was Russkaya dusha – Russian soul. This is a big concept for them, ask any Russian about it and they suddenly get very animated. For me though, it was also a cipher to talk about my interest in Romanticism: the link between the human spirit and the wonder of creation. This link between feeling and landscape was brought out brilliantly in Vasily Grossman’s book ‘Life and Fate’, an epic of the Russian nation centred around the battle of Stalingrad. Suddenly at the end of a long piece of physical description about the Russian steppe, he slips in the metaphysical point of what he is talking about: ‘The earth was vast, even the great forests had both a beginning and an end, but the earth just stretched on for ever. And grief was something equally vast, equally eternal.’

Only a Russian could have written that line. As my crazed oligarch, Sergey, explains: “This Russian sadness is actually a truer appreciation of humanity. You see you can only be truly happy once you have been truly sad. A Russian understands this – that all emotions are just facets on the jewel of the human soul! In Western Europe you have this obsession with happiness that demeans that jewel; you see only half of it, but the Russian soul has many sides.”

Whatever you make of that, the line rang true for me and I wanted to explore Russkaya dusha and Romanticism more through Sergey and his relationship with his former lover Lara Maslova.

So why this fascination with Russia? The country has always gripped me, in a naively romantic way – the reality of life for most Russians for most of their history has been anything but romantic. However, everything did always happen there in a much more dramatic fashion than in Western Europe, usually because, whatever they do, the Russians always seem determined to do it the hard way. They are the world champions at suffering.

Consequently, I plunged into Russian literature: Tolstoy, Gogol, Pasternak, Sholokov, Pushkin, Grossman, Chekhov, Solzhenitsyn, Zemyatin. Despite their rather forbidding reputation, I found these writers marvellously readable yet very insightful about life: they were forever telling me things I knew but had not realised that I knew. They had such beautifully observed portrayals of the whole of life – characters, politics, landscape. Everything was in such depth but never in that boring, self-indulgent way that a lot of self-consciously ‘clever’ Western writers have. Russian writers seemed to know that life was complicated enough without dressing it up or affecting experimental literary styles. They felt that it was their duty to lay it out for us clearly, piece by piece, so that we can get a truer understanding of what is really going on, so that we can understand a greater reality, beyond reality.

Russians have had enough suffering that they have plenty of real stuff to write about and also don’t feel the need to affect ennui, another Western trait that annoyed me. Russian characters are not flaneurs drifting through life; they are real people trying to make the best of difficult circumstances. The writers seemed to be saying: ‘Every aspect of life is wonderful and special and precious, and I am going to show you that by recording it meticulously and explaining it beautifully.’

So the whole of December is inspired by and dedicated to Russian literature, the plot is full of quotes from my favourite writers and I have used their names and the names of characters from their books in tribute to them. As Sergey explains, literature has been used by Russians over the centuries to explore who they are as a nation, each book is a journey into their subconscious.

Why have they needed to explore themselves in this way? Well, Solzhenitsyn said in his 1970 Harvard lecture: “Russia is neither European nor Asian but Russian.” Any country with a double-headed eagle as its emblem must be slightly schizophrenic. They have always sat on the fault line between these two cultures and have never been quite sure what they are. So the development of their literature in the nineteenth century was an important means of working it out and gave them that sense of having a duty to explain things clearly.

The upshot of all this for my writing style is that I try to write what I call ‘mindful violence.’ What does that mean? What I am trying to do is to occupy the middle ground between thoughtful (but not intellectual) writing and action. When I was a teenager I loved thrillers: Alaistair McLean, Desmond Bagley, Frederick Forsythe, Wilbur Smith, Len Deighton, Craig Thomas. I just lapped them up. After a while though I wanted more depth than a purely plot based genre offered.

Overall then in December, what I am trying to do is to bring the two styles together: a gripping plot but with some decent characterisation and lots of ideas about literature, history and politics thrown in. Whether I achieve it is up to you to judge.